Kim Chul: The poet who said sorry

The end of 2014 saw a deeply silly furore over Seth Rogen’s The Interview, an otherwise forgettable, ‘satirical’ account of two bumbling idiots deployed by the FBI to assassinate North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. The film prompted rage from Pyongyang.

The whole affair was interesting to me because it was something of a rarity. North Korea often gets cross with other nations – that isn’t rare – but it’s unusual for the North Korean elite to get involved in cultural matters beyond their own border. Indeed, far more fascinating/horrifying censorship stories have emerged from within the hermit kingdom.

Take the life of North Korean poet Kim Chul.

Kim Chul was a prominent North Korean poet in the 1950s and early 1960s, around the time Kim Il-sung and the Workers’ Party of North Korea was beginning to throttle the country under a new dictatorship. Like all great poets, Kim Chul wrote poems which were subtle, wise, succinct, and often beautiful. He was nicknamed “the Pushkin of Korea” by the people. He was particularly renowned for his lyrical poetry about love.

However, some of his work was politically loaded. “A Military Jacket Button” tells of a soldier returning home after the 1950-53 Korean War, and a motherless baby sucking on a button of the soldier’s uniform, mistaking it for its mother’s nipple:

The poem tells of the misery endured by the North Korean people by the Korean War. Critically, it was a direct challenge to the Workers’ Party’s central ideology. In North Korea, propaganda tells of how the heroic Koreans drove the American imperialists from their lands. The Korean War, goes the official line, was a glorious victory, to be exalted by all. “A Military Jacket Button” was swiftly banned.

The authorities rounded on Kim Chul. His relationship with a Russian woman began to draw their attention. Upping the pressure on Kim Chul, the authorities issued an order for their divorce, but Kim Chul refused to comply. Eventually, he was told to either divorce his partner or give up his Party membership.

An outraged Kim Chul said he would rather not be a member of the Party if such oppression was the price. The outcome was sadly predictable: the Russian was forcibly sent home and Kim Chul was sentenced to a lifetime of hard labour, along with his young son (in North Korean law, families of “criminals” are often also punished).

As the years passed by, Kim Chul continued to work in the mines, watching his son struggle as he grew up, almost permanently exhausted and suffering. The poet fell into depression. Gnawed by guilt over his innocent son’s hard life, Kim Chul began to accept that art in North Korea meant little unless used as a tool of propaganda, as a way to exalt the Party.

As his son approached adulthood, Kim Chul decided to compose an apology to his homeland, only to find getting his work published by the state was virtually impossible. He had effectively been erased from the history of North Korean literature.

Distraught, Kim Chul eventually wrote a poem titled “Forgive Me”, in which he pleaded for forgiveness:

Spotting a chance for a propaganda coup, Kim Jong-il accepted Kim Chul’s apology. The poet and his family were invited back to Pyongyang and given a luxury apartment in a forty-story building in the Ryugyong-dong, Botong-gang area. Kim Chul’s children were enrolled in the school of literature at Kim Il-sung University; they were to follow the example of their poet father, to sing eternal praises to the Party.

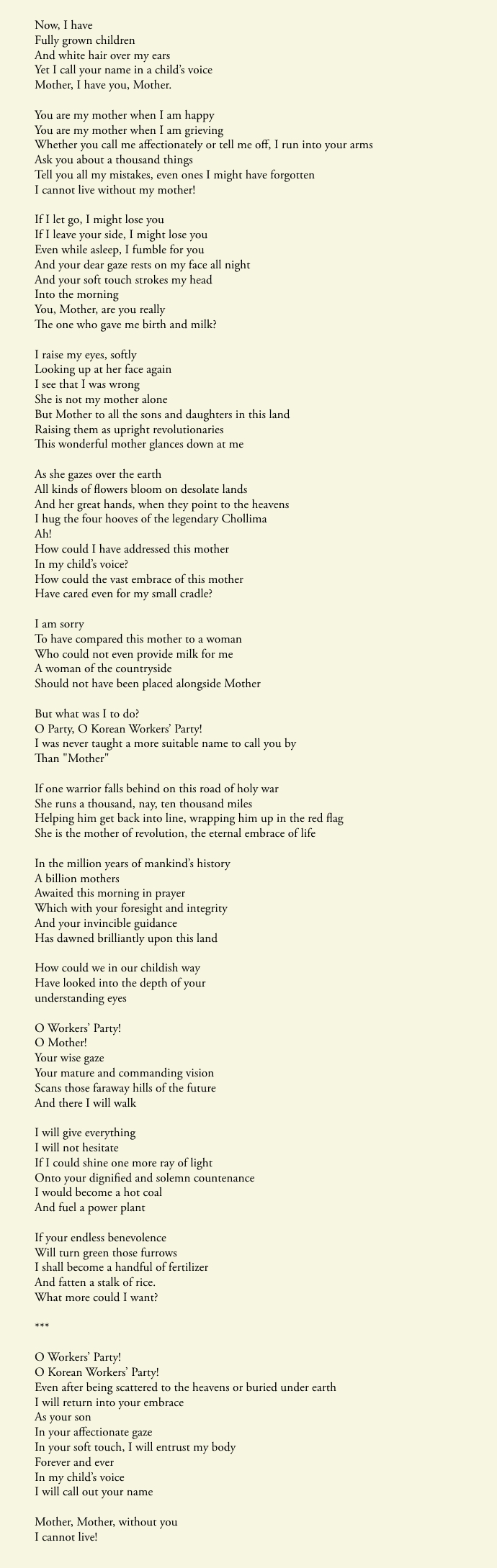

Kim Chul gushed his thanks in another poem, “Mother”, a hymn which is now required learning for all North Koreans:

Chris Greenhough

Tags: censorship, kim chul, north korea, Poetry